Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome or IBS is a multi-faceted gastrointestinal complication becoming increasingly prevalent in children and adults. IBS is an issue estimated to affect 10-15% of the global population (1). Furthermore, 20-40% of all gastrointestinal related doctor’s visits are due to IBS (1). Sufferers of this unpredictable and occasionally debilitating disorder are commonly given a diagnosis however, there is no cure besides lifestyle modifications. The exact cause of IBS is unknown, however it is thought to be related to the gut-brain axis which can increase and/or decrease peristalsis in the gut, which may cause symptoms of diarrhea and/or constipation, respectively (1). Factors which disrupt the normal gut flora, such as antibiotic use, can play a role in the onset and/or persistence of IBS (2). The human body contains about 2-6 pounds of beneficial, or mutualistic, bacteria which are vital to protecting the body against dangerous pathogens (2). These beneficial bacteria are an important population in the human gut microbiome. These bacteria aid in the digestion and absorption of food, and the production of some vitamins, anti-inflammatory compounds, and short-chain fatty acids, among others. When the gut microflora is in a dysbiotic state, ingesting beneficial bacteria as probiotics may help regain symbiosis. Probiotics are live microorganisms said to confer health benefits onto their host when taken in large enough doses (3). Probiotics are found in food (functional foods), supplements, drinks, skin care products, and are increasing in popularity. The realm of probiotic research is quite young, fairly complex, yet fascinating. Although conclusive research is still limited, recent clinical studies report efficacy of probiotics in the therapeutic management of IBS.

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus Species as Probiotics

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are two of the most prevalent species in a healthy human’s microbiome, even soon after birth (4). These bacterial species are also commonly found in food products as well as breast milk (5). Furthermore, infection by these bacteria are extremely rare, estimating a mere 0.05%-0.4% of cases (5). Additionally, these cases are attributed specifically to immunocompromised individuals and by no means represent the majority of the population (5). The prevalence of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species in normal human gut microflora, application in food products, and safety not only support these bacteria for use as probiotics, but has propelled researchers to conduct numerous studies to investigate their potential roles in reducing IBS symptoms.

Lactobacillus salivarius UCC4331 and Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in IBS

A study in 2005, looked at two specific strains of bacteria, Lactobacillus salivarius UCC4331 and Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and their effectiveness in reducing IBS symptoms and cytokine profiles (4). Sixty-seven subjects enrolled and completed the 8-week parallel design study. These participants had been diagnosed with the Rome II criteria for IBS, met all pre-protocols (clinically significant abnormalities in blood count, serum chemistry, and quantitative serum immunoglobulin levels were excluded), and maintained these strict protocols throughout the study. Subjects received one of the three drinks: a malted milk drink with Lactobacillus, a malted milk drink with Bifidobacterium, or a malted milk drink with no added probiotics (placebo). The two probiotic drinks each contained 1 x 1010 CFU (10 billion) viable bacterial cells. Furthermore, the drinks were identical in taste, consistency and appearance. The subjects were blinded to the randomization of the drinks and directed to consume the drink once in the morning for 8 weeks. They were also directed to record changes in IBS-related symptoms and stool characteristics daily. After the 8 weeks, participants discontinued the drinks, however, they continued to record their symptoms and stool characteristics. IBS symptoms which were assessed weekly were abdominal pain, bloating, and bowel movement difficulty. A quality of life assessment was also given to participants during the randomization and during the 4 week wash-out period. Blood samples were taken before, during, and after the trial to assess basal cytokine production from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in particular. Stool samples were also taken during the trial and after the treatment.

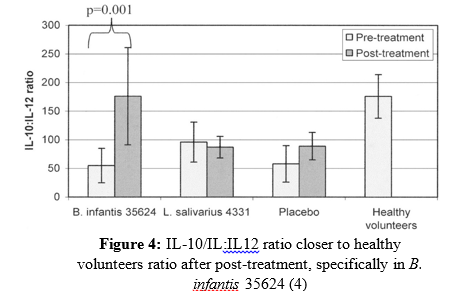

Several significant results were seen in relation to Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium probiotics and their effectiveness in reducing IBS-related symptoms. First, abdominal pain had subsided more with both probiotic treatments compared to the placebo (Figure 1). Second, a reduction in bloating was also seen specifically with the Bifidobacterium species as opposed to the placebo and Lactobacillus species (Figure 2). Third, bowel movement difficulty was also decreased in those consuming the probiotic treatments, again more significant results were seen in the Bifidobacterium species (Figure 3). Finally, quality of life  had improved more significantly in participants receiving the probiotic treatments. A significant quantitative measurement was also observed in those undergoing the probiotic treatment versus the placebo. PBMC IL-10:IL-12 production is used as a common cytokine biomarker in IBS sufferers, where the IL-10:IL-12 ratio is significantly reduced, and inflammation being higher in those with IBS compared with healthy individuals (4). Interestingly, this study shows subjects who consumed the Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 treatment had an IL-10:IL-12 ratio much closer to normal individuals during post-treatment (Figure 4). Clearly, the Bifidobacterium species exerted more beneficial effects including the promotion of anti-inflammatory cytokines in IBS participants in comparison to the Lactobacillus and placebo. The results from this 2005 study, set the stage for further human trials, especially using Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 to aid in the treatment of IBS.

had improved more significantly in participants receiving the probiotic treatments. A significant quantitative measurement was also observed in those undergoing the probiotic treatment versus the placebo. PBMC IL-10:IL-12 production is used as a common cytokine biomarker in IBS sufferers, where the IL-10:IL-12 ratio is significantly reduced, and inflammation being higher in those with IBS compared with healthy individuals (4). Interestingly, this study shows subjects who consumed the Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 treatment had an IL-10:IL-12 ratio much closer to normal individuals during post-treatment (Figure 4). Clearly, the Bifidobacterium species exerted more beneficial effects including the promotion of anti-inflammatory cytokines in IBS participants in comparison to the Lactobacillus and placebo. The results from this 2005 study, set the stage for further human trials, especially using Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 to aid in the treatment of IBS.

Another study published in 2006, expanded on the work O’Mahony et al. (4) had done with Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and IBS (6). Since this  particular strain had shown excellent efficacy in the treatment of IBS previously, Whorwell et al. (6) set out to conduct a more large-scale study particularly with women, to determine an optimal dosage in an encapsulated form of the probiotic bacteria B. infantis 35624. A total of 330 women subjects from 20 different primary care centers in the United Kingdom completed the study, all of which were IBS sufferers by the Rome II criteria. For four weeks, randomized and blinded participants were subject to one of the following treatments: B. infantis 35624 in a freeze-dried encapsulated form: 1 x 106 CFU (1 million), 1 x 108 CFU (100 million), and 1 x 1010 CFU (10 billion) or a placebo form. Participants were asked to record their observations of IBS symptoms on a daily basis throughout the study. Throughout the study, the 1 x 108 CFU dose appeared to be the most effective in reducing IBS symptoms compared to

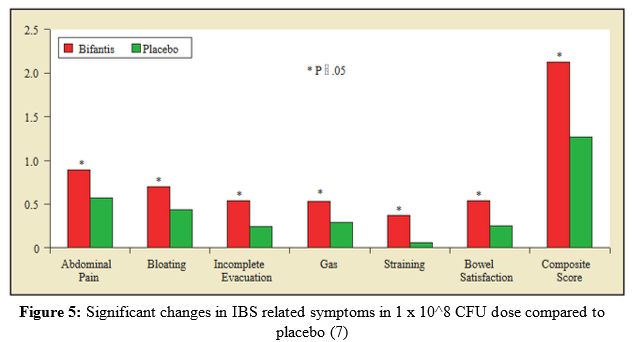

particular strain had shown excellent efficacy in the treatment of IBS previously, Whorwell et al. (6) set out to conduct a more large-scale study particularly with women, to determine an optimal dosage in an encapsulated form of the probiotic bacteria B. infantis 35624. A total of 330 women subjects from 20 different primary care centers in the United Kingdom completed the study, all of which were IBS sufferers by the Rome II criteria. For four weeks, randomized and blinded participants were subject to one of the following treatments: B. infantis 35624 in a freeze-dried encapsulated form: 1 x 106 CFU (1 million), 1 x 108 CFU (100 million), and 1 x 1010 CFU (10 billion) or a placebo form. Participants were asked to record their observations of IBS symptoms on a daily basis throughout the study. Throughout the study, the 1 x 108 CFU dose appeared to be the most effective in reducing IBS symptoms compared to  the other treatments and placebo. There were significant changes in symptoms from the start of the 4 week trial to the end, in the 1 x 108 CFU dose group versus the placebo group (Figure 5) (6). Furthermore, a significant percentage of participants who received the 1 x 108 CFU dosage answered “yes” to a question pertaining to an overall decrease in IBS related symptoms in comparison to the other doses and placebo (Figure 6) (6). These findings may be surprising, as in most studies with probiotics the higher dosage is usually more effective or at least just as effective as a dose somewhat smaller. However, in this study the least effective dose happened to be the highest dose. Furthermore, O’Mahony et al. (4) used the same dosage of 1 x1010 CFU viable cells in a non-encapsulated form, that showed superb effecacy in treating IBS symptoms. Further post-study experiments in the study by Whorwell et al. (6) discovered a fault in the 1 x1010 CFU probiotic capsules, where coagulation into a glue-like form when exposed to stomach acid had occurred only with this dosage. This would completely inhibit the growth of this bacterium in the gut, which explains the conflicting results between the two studies discussed. This factor may render this study fairly inconclusive; however, it brings up an important limitation to the development of probiotic supplements as a whole.

the other treatments and placebo. There were significant changes in symptoms from the start of the 4 week trial to the end, in the 1 x 108 CFU dose group versus the placebo group (Figure 5) (6). Furthermore, a significant percentage of participants who received the 1 x 108 CFU dosage answered “yes” to a question pertaining to an overall decrease in IBS related symptoms in comparison to the other doses and placebo (Figure 6) (6). These findings may be surprising, as in most studies with probiotics the higher dosage is usually more effective or at least just as effective as a dose somewhat smaller. However, in this study the least effective dose happened to be the highest dose. Furthermore, O’Mahony et al. (4) used the same dosage of 1 x1010 CFU viable cells in a non-encapsulated form, that showed superb effecacy in treating IBS symptoms. Further post-study experiments in the study by Whorwell et al. (6) discovered a fault in the 1 x1010 CFU probiotic capsules, where coagulation into a glue-like form when exposed to stomach acid had occurred only with this dosage. This would completely inhibit the growth of this bacterium in the gut, which explains the conflicting results between the two studies discussed. This factor may render this study fairly inconclusive; however, it brings up an important limitation to the development of probiotic supplements as a whole.

Limitations of Probiotic Research for IBS

The cause of IBS is still somewhat of a mystery to the scientific community. Likewise, probiotics’ role in the treatment or reduction of symptoms in IBS is also largely unknown. The majority of studies involving IBS and probiotics focus on gathering qualitative results from participants rather than quantitative measures. Although notable, qualitative results are not enough to elucidate the mechanisms of probiotics actions, and thus, may limit their effectiveness in the treatment of IBS. Furthermore, qualitative results rely on the accuracy of subjects reporting their own improved symptoms, which are sometimes inaccurate or could be attributed to the placebo effect. Certainly, various studies suggest that probiotics confer more than just a “placebo effect” in the treatment of IBS. This can be confirmed by the error in the study by Whelman et al. (6). The group which received the 1 x 1010 CFU dose clearly experienced no reduction in IBS symptoms, which later made sense after the capsule error was discovered (6). Further, the study by O’Mahony et al. (4) clearly shows improvements in quantitative biomarkers for the anti-inflammatory cytokine ratio IL-10:IL-12 in PBMCs from IBS subjects undergoing probiotic treatment (4).

Various factors that contribute to probiotics efficacy make designing experiments difficult. Some of these factors include: culturing an effective probiotic strain as specific strains are responsible for different health effects, administering a high enough effective dose, choosing an effective vehicle for the probiotic in order for it to proliferate in the large intestine, administration frequency, when the dose should be administered (before, during, after meals), and the duration of administration (8). The study of microbiology is vast and complex in itself. There are trillions of different bacteria, all of which can undergo new morphology under various conditions that can sometimes be a mystery to humans. The efficacy of probiotic bacteria is strain-specific, meaning one strain of bacteria, for example, may reduce diarrhea whereas another strain may reduce bloating. However, knowing which probiotic strain to conduct studies with is extremely challenging. Historically, it has been easy for mankind to study and understand harmful bacteria, as their virulence is apparent and causes acute health effects. However, probiotics seem to contribute less acute effects and more long-term health outcomes that are subtle. The need for long-term studies and the limitations that coincide with those long-term experimental designs is a huge obstacle for probiotic research.

Clinical Support in Treating IBS with Probiotics

Regardless of the lack of conclusive scientific research, many clinicians and specialists support the use of probiotics for IBS. As mentioned before, IBS has no known cure, although lifestyle modifications are recommended for the management of its symptoms. Research has demonstrated the safety of probiotics in immunocompetent individuals, which is the main reason clinicians feel confident prescribing them to patients (7). The minimal side effects associated with probiotics are also quite attractive both to patients and clinicians, as most pharmaceutical use is accompanied with side effects which may discourage patients from taking them (7). Even if there’s a slight improvement in IBS symptoms from a probiotic supplement, this is a huge achievement and may dramatically improve quality of life in IBS sufferers.

Multi-species Probiotics

It is important to consider the potential increased efficacy of multi-species probiotic cocktails, which are supplements with multiple probiotic strains (8). This was shown in a 2007 study conducted at the University of Helsinki in Finland (9). A total of 86 participants with the Rome II criteria for IBS were randomized and given a 5 month intervention of a daily probiotic milk-based drink containing 1 x 107 CFU of each of the following: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, L. rhamnosus Lc705, Propionibacterium freudenreichii ssp. shermanii JS and Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis Bb12. Participants were asked to record any observations related to IBS symptoms throughout the trial. Results from this study showed a 37% decrease in IBS symptoms from baseline in participants consuming the probiotic treatment as opposed to the placebo that only conferred a 9% decrease in symptoms from baseline. This study showed a significant improvement in IBS symptoms with a multi-species probiotic cocktail containing 4.8 × 109 live bacterial cells.

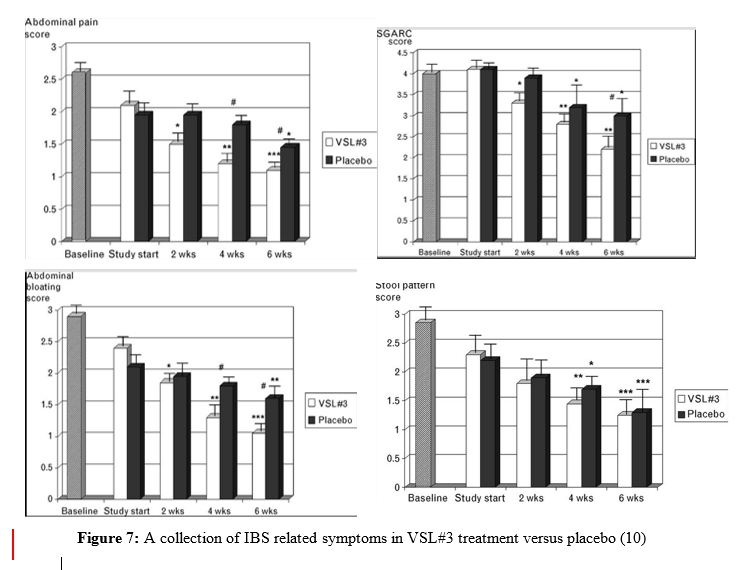

A more recent study conducted in 2010 examined the effects of a clinically prescribed probiotic cocktail, VSL#3 in the treatment of IBS in sixty-seven children subjects (10). VSL#3 contains 450 billion total viable cells composed of the following: Bifidobacterium breve, B longum, B infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. casei, L. bulgaris, and Streptococcus thermophiles (notice strain number was not publicized). This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study included two groups of children, ages 4-11 and 12-18, and lasted a total of 12 weeks. The younger group was directed to take one sachet of VSL#3 once a day whereas the older group was given 2 sachets twice a day, for 6 weeks. There was a 2-week washout period to diminish any carryover effects from the probiotic treatment. Then, subjects returned to the clinic and were given the placebo to take for the next 6 weeks. Results from this study in children were similar to previous studies that had been conducted in adults. During the 6 weeks of the VSL#3 treatment, subjects had improved IBS symptoms; however, symptoms returned during the 6-week placebo trial (Figure 7). This experimental design was more innovative and long-term compared to previous studies, which strongly supports the use of these probiotics for IBS patients. Furthermore, this study examined IBS in children, whereas previous studies had only looked at adults. This suggests there is potential for use of probiotics in the treatment of IBS regardless of age.

Recommendations for the Public

Probiotics and functional foods have become a health trend in recent years. In 2015, the probiotic market reached USD $36.6 billion and is expected to exceed USD $64.6 billion by 2023 (11). With the market expanding, companies are developing multiple probiotic products usually with minimal research to support their full efficacy. The FDA is not involved in the regulation, testing or labeling of supplements, thus, their safety and effectiveness is assumed until proven otherwise. This potentially allows the opportunity for companies to deceive consumers to make more profit. Supplement companies are not required to conduct research to prove a supplements effectiveness; thus, the consumer must rely on reviews, word of mouth or their own experiences when evaluating a supplement’s effectiveness. Higher CFUs are assumed to confer more health benefits, however, just a 100 million CFU dosage was shown to be effective in reducing IBS related symptoms (6). Again, strain is important when evaluating dosage amount. Talking to a doctor or GI specialist about incorporating probiotics into an IBS regimen is best when deciding whether or not to take a probiotic. Furthermore, many insurance companies will cover probiotic treatments prescribed by a doctor or specialist.

As stated previously, there are still a lot of unknowns about the role of probiotics in the treatment of IBS. At this point in time, only a few controlled trials suggesting probiotic efficacy in the treatment of IBS exist, most of which lack quantitative measurements to support their efficacy. In saying this, more conclusive evidence must be obtained through additional rigorous, long-term, and well-designed experiments. However, it is important to note that probiotics have been used in alternative medicine for centuries (12). From 2000-2010, over 5,000 articles were published in medical literature pertaining to probiotic therapeutic usage in various medical conditions (12). The studies outlined in this paper are just a few of the findings which support the usefulness of probiotics to improve quality of life for many IBS sufferers. The qualitative results gathered from these findings are significant and have shown improved IBS-related symptoms in subjects. Because of these modest yet significant, results, future probiotic research is warranted.

Reviewed by Christopher Blesso, Ph.D. Assistant Professor. Department of Nutritional Sciences. University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Thanks for this…very informative