Introduction

Sugar – a diverse, versatile and pleasurable substance. A recent New York Times article published in September 2016, revealed the dark truth about the sugar industries role in shaping dietary guidelines in the 1990s, by down-playing sugar’s role in obesity and disease and forcing the blame onto fat (1). By the late ‘90s, just about everything was low-fat or fat-free. Food was no longer as palatable or satisfying to consumers, because fat is flavorful and contributes to satiety. With fat excluded from the scenario, sugar was added to everything the food industry had to offer – from salad dressings to frozen meals. By 1990, the American Heart Association further validated the “low-fat” recommendation by labeling newly low-fat, high sugar foods with a “heart healthy” seal of approval (2). However, fresh foods like fruits and vegetables were excluded from this endorsement. The food industries profits soared. Consumers began to eat more per sitting, as the more satiating macronutrient, fat was excluded from most foods. Furthermore, sugar was cheaper to use compared to fat which made processed foods an even cheaper alternative to fresh foods (2). It was the perfect storm for the sugar and food industry alike. With multiple health organizations, health care professionals, and the media on board, sugar became one of the most addictive legal substances still plaguing our population’s health today.

Defining Addiction

The brain is responsible for maintaining normal functions of the body through various neural pathways. Homeostatic signaling regulates normal processes which include the motivation to eat when hungry or refrain from eating when one has just finished a large meal (Blesso). However, homeostatic signals are not the only signals that affect food consumption and many times they’re overridden by multiple other pathways (Blesso). Conversely to homeostatic regulation, hedonic signaling is responsible for perceiving pleasure and is a reward-associated cascade that encourages life-promoting activities (Blesso). Hedonic signaling is much more interesting, pleasurable and rewarding compared to homeostatic signaling (Blesso). Therefore, hedonic signaling is easier to exploit and manipulate. Normal hedonic pathways can easily become high-jacked by various highly pleasurable things such as: drugs, sex, food, shopping, gambling, alcohol, etc. The result of these highly pleasurable activities or substances cause an over flooding of opioids, which block pain and confer anti-depressant effects and free dopamine which produces a “euphoric” effect in the body (4).

Dopamine and opioids are important neurochemicals in the evolution of reinforcing positive, natural behaviors for survival, therefore their production and signaling are highly regulated. However, addiction starts to override normal behaviors when excessive dopamine release is repeated over a long period of time (4). Addiction is described by the American Psychiatric Association as a dependence on a substance or activity (4). Bingeing, withdrawal, craving, and sensitization are the corner stones in diagnosing addiction (4). Numerous rat studies have been conducted to better understand the question – is sugar an addictive substance?

Quantitative Evidence of Sugar as an Addictive Substance

An operant conditioning study published in 2004 by Avena et al., was designed to test the effect of sugar deprivation in rats (5). The experimental group was exposed to a 25% glucose solution for 30 minutes per day for 28 days, with an additional 11.5 hours of glucose access per day, for a total of 12 hour access of glucose solution per day (5). The control group was exposed to the same conditions without the additional 11.5 hours of glucose access per day (5). The rats were then deprived of glucose for two weeks and fed only normal rat chow (consisting of mainly fat and protein) (5). After the two weeks, both groups were exposed to two water bottles during their regular rat chow feeding: one bottle with glucose solution and one of just water. The experimental group which had 12 hours of total exposure to glucose solution expressed a heightened motivation to bar press for the glucose solution versus the control group (Figure 1) (5). This data suggests that a longer exposure to sugar substances could potentially play a role in the motivation to consume more sugar when given the opportunity, also known as craving-like behavior, a criteria for addiction (5).

A four week study published in 2005 and conducted by Wideman et al., was developed to find evidence of withdrawal and relapse in glucose deprived rats (6). A control group of 6 rats and an experimental group of another 6 rats underwent habituation for 14 days (6). In this habituation phase, circadian rhythms of the rat’s body temperatures were recorded every five minutes for a normal baseline to compare further data to (6). In the first week, both control and experimental rats underwent the same conditions of being fed normal rat chow (6). However in the second week the experimental group was exposed to an additional two water bottles: one with water and one with a 25% glucose solution (6). In the third week, no glucose was administered to either group, just rat chow (6). In the fourth week, the same procedure from week two was repeated but only in the experimental group (two bottles: one with water, one with a 25% glucose solution and normal rat chow) (6). After the last day of the fourth week, rats were deprived of glucose for 12 hours and then sacrificed – blood glucose levels were then taken and recorded (6). Various significant results were gathered from this study. First, a significant drop in body temperature in the experimental group compared to the control group during week three was observed (6). Keep in mind, during week three, the experimental rats were deprived of glucose after having exposure to the 25% glucose solution throughout week two. However, during week four when 25% glucose solution was administered again, the experimental group had comparable body temperatures to the control group (Figure 2)  (6). The significant drop in body temperature shown in week three, (when rats underwent abstinence from the glucose solution) mirror the same hypothermic effect addicts experience during withdrawal from highly addictive drugs (6). As stated by Wideman et al., these hypothermic effects are some of the most reliable forms of evidence when diagnosing withdrawal from addictive substances (6). To further support the idea of addiction in this experiment, rats drastically increased their glucose consumption throughout the duration of week two and four when exposed to the glucose solution (Figure 3)

(6). The significant drop in body temperature shown in week three, (when rats underwent abstinence from the glucose solution) mirror the same hypothermic effect addicts experience during withdrawal from highly addictive drugs (6). As stated by Wideman et al., these hypothermic effects are some of the most reliable forms of evidence when diagnosing withdrawal from addictive substances (6). To further support the idea of addiction in this experiment, rats drastically increased their glucose consumption throughout the duration of week two and four when exposed to the glucose solution (Figure 3)  (6). This steady compulsory increase in substance (glucose) indicates binge-like behavior, also characterized in drug addiction (6). Body weight increased in both groups as a normal parameter in week one through three, however during week four the experimental groups body weight increased much more than the control group (Figure 4)

(6). This steady compulsory increase in substance (glucose) indicates binge-like behavior, also characterized in drug addiction (6). Body weight increased in both groups as a normal parameter in week one through three, however during week four the experimental groups body weight increased much more than the control group (Figure 4)  (6). Furthermore, total calorie intake was much higher in the experimental group during week two and week four when the glucose solution was administered (Figure 5)

(6). Furthermore, total calorie intake was much higher in the experimental group during week two and week four when the glucose solution was administered (Figure 5)  (6). At the end of the experiment, the experimental group’s blood glucose had a mean of 156.4 dL versus the control groups of 140.0 dL (6). These elevated blood glucose levels are the same lab measurements health care professional use to diagnose type two diabetes in humans.

(6). At the end of the experiment, the experimental group’s blood glucose had a mean of 156.4 dL versus the control groups of 140.0 dL (6). These elevated blood glucose levels are the same lab measurements health care professional use to diagnose type two diabetes in humans.

Qualitative Evidence of Sugar as an Addictive Substance

Aside from quantitative results, qualitative behavioral results were also observed in Whiteman’s study – the results were quite significant (6). Experimental rats showed major signs of nervousness and withdrawals during week three (during abstinence of glucose solution) including: body shakes, teeth chattering, standing on two legs and gnawing on the bars of the cage, and attempts to bite research assistants when they picked up the rats to weigh the animal (6). However, these behavioral signs were completely absent in the control group (6). Also, when the glucose solution was reintroduced in week four, rats immediately ignored their rat chow and went for the glucose solution (6). This shows a relapse in withdrawal symptoms observed in the week prior. Not only did rats immediately go for the glucose solution and ignore their rat chow, but the rats consumed very high amounts of the glucose solution on day one of week four which is denoted with a black arrow on Figure 3 (6). This shows obvious signs of binge-like behavior also indicative to addiction (6).

Drugs, Sugar and Neurotransmitter Release

Caloric and non-caloric substances that confer a sweet taste strongly activate the mesolimbic dopamine system which induces reinforcement effects in the brain (Blesso). The deprivation and administration of sugar and addictive drugs share many of the same neurological pathways (4). One of the main characteristics of drug abuse involves a repeated release of extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (4). Repeated releases of large amounts of dopamine actually decrease the available dopamine receptors in the brain and increase the amount of opioid receptors (4). This explains the onset of depression when abusers build a tolerance to an addictive drug, and therefore must take more of the drug to generate the same “euphoric” effect (4). Various studies have suggested that dopamine binding is altered on D1, D2, and D3 receptors in drug and sugar addiction (4). Opioid receptors are also modified in addiction, where mu-receptor sensitization increases during the administration of addictive drugs such as, morphine or cocaine (4). Studies have shown this same sensitization in mu-receptors in rats given excessive access to sucrose for just three weeks (4).

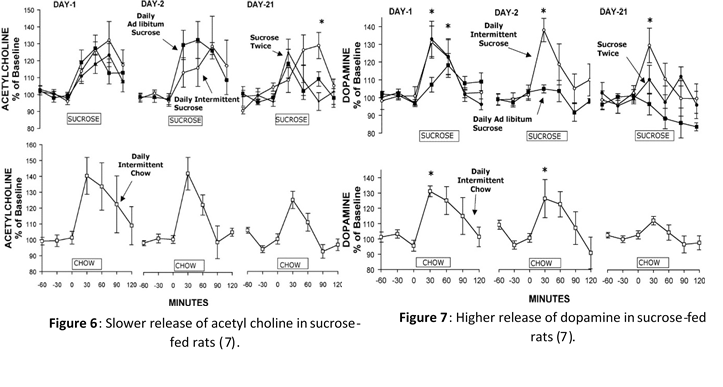

Opioid modification is the main culprit in withdrawal symptoms (4). These withdrawal pathways are linked to a decrease in the release of dopamine and an increase in acetyl choline (4). These changes in neurological pathways are seen in sugar- and drug-deprived subjects (4). Another study conducted by Rada et al. (7), shows extracellular acetyl choline levels increase faster when sucrose naive rats consume sucrose (7). Acetylcholine is known to be an anorexigenic neurotransmitter, thus normal rats who consume sucrose have a faster release of acetylcholine, making them consume less sucrose and calories. However, in rats that had been given access to sucrose for 21 days, acetyl choline release was delayed and therefore, when exposed to sucrose, calorie consumption was increased and rats showed binge-like characteristics (7). This phenomenon was coupled with an increase in extra cellular dopamine and a decrease in acetylcholine, when rats with repeated access to sucrose for 21 days was exposed to sucrose (Figures 6 and 7) (7). Thus, satiety was delayed and rats consumed higher amounts of sugar and calories, and gained more weight (7). This increase in extra cellular dopamine is the same reinforcing-effect addictive drugs have on the brain in humans (7).

A study conducted at University Bordeaux 2 in France, was designed to test rats preference for saccharin-sweetened solution versus intravenous cocaine (8). Interestingly, this study looks at saccharin as opposed to sucrose and suggests sweet taste regardless of caloric density can be just as addictive. Results of this study showed that although rats were “rewarded” by consuming the cocaine, rats preferred or “liked” saccharin and were also willing to work for or “wanted” saccharin more over cocaine (8). In fact, 94% of animals in their trial preferred the intense sweet taste from saccharin, a non-caloric sweetener, to cocaine, a highly addictive drug (8). These significant results show, the intense sweetness from the saccharin surpassed the cocaine-associated reward (8). The study further confirms previous studies with similar objectives, however using primate subjects (which respond more like human subjects) (8). In the other studies, primates showed preference for cocaine over food. However, the food in these studies failed to have a high level of sweetness, which could explain these contrasting results (8).

Considerations for Sugar Addiction Research

Researchers suggest that sugar addiction is real and shows similarities in dependence, neurochemical pathways and behaviors when compared to addictive drugs (7). The studies described in this paper are only a few that demonstrate these similarities. However, it’s important to consider sugar addiction as a young area of research and a somewhat inconclusive phenomenon. Almost all early research begins by conducting pre-clinical studies on laboratory animals to see if there’s evidence to further pursue research on human subjects. Although many studies with rats have shown results of sugar addiction, further human trials are needed to develop conclusive evidence for sugar addiction in humans. Some human studies have been conducted which have shown sugar as a coupled addiction to those also suffering from substance abuse and/or eating disorders (7). However, studies involving subjects without pre-existing addictions is lacking. Therefore the hypothesis of sugar being as addictive as drugs, or addictive at all, is still controversial.

Applied Considerations for Sugar Addiction

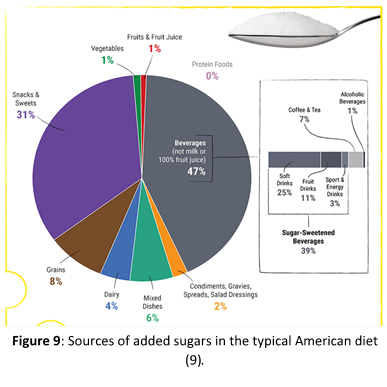

The rising prevalence of obesity, type two diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer suggests that changes in the food system, and thus, changes in eating patterns play a huge role in the onset of various disease states. It’s widely accepted that the typical western diet, high in sugar, fat and calories contributes to obesity, which leads to further health complications. Furthermore, the prevalence of processed and convenience foods happens to be coupled with high carbohydrate density. The detrimental health effects of consuming sugar in excess has been touted by various health organizations. The recent Dietary Guidelines recommends no more than 10% of daily calories coming from added sugars (9). Obviously, this recommendation was added because of the increasing popularity of added sugars in nearly anything processed, even items one would not expect (9). The most recent NHANES survey, published by the CDC concurs, Americans’ are consuming more than the recommended amount of added sugars (Figure 8) (10). Statistics from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics suggest an even scarier truth. Health organizations, health promotion/campaigns and health care providers consistently publicize the prevalence of added sugars in sweets, sweetened beverages and snacks, yet they happen to be the largest sources of added sugars (Figure 9) (9). In fact, in the past two years, spending on disease prevention and health promotion in the U.S has been well over $700 million, according to the CDC’s budget report (11).

(10). Statistics from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics suggest an even scarier truth. Health organizations, health promotion/campaigns and health care providers consistently publicize the prevalence of added sugars in sweets, sweetened beverages and snacks, yet they happen to be the largest sources of added sugars (Figure 9) (9). In fact, in the past two years, spending on disease prevention and health promotion in the U.S has been well over $700 million, according to the CDC’s budget report (11).

Furthermore, a health survey conducted by Healthline, a trusted medical information and health advice site, found that out of 3,223 Americans, 62% of them were concerned about the health effects of sugar and 40% of them felt guilty about indulging in too much added sugar versus carbohydrates or fats (12). This survey suggests that consumers are well aware of the harmful effects of consuming added sugars in excess – so why do they continue to do so? Perhaps sugar addiction could answer this question.

Recommendations for the General Public

Clearly, consuming sugar in excess is a huge health concern for a magnitude of reasons. The underlying issues behind added sugar’s prevalence in the food system encompass far more than what most consumers may want to believe. Politics, governmental spending, lobbying, advertisement, and public policy all play a major role in the battle between the processed food industry and the health and well-being of its consumers. For many years, the processed food industry has exploited it’s consumers for billions of dollars and the power to control governmental policy as they wish. However, there is a movement to take back the control, take back health, and take back the processed food industries profits and share them with hard-working farmers and companies which promote true nutrition, health and wellness.

First and foremost, consumers must focus on appreciating flavors besides “sweet”. The body produces energy from the glucose molecule and therefore we’ve evolved to like foods which are sweet – it’s quick energy to promote further living. Furthermore, the flavor of “sweet” usually means a food is safe to eat, versus sour or tart foods which are usually toxic when consumed. These facts alone, lay the groundwork for defining sugar as addictive. However, glucose can be generated from the other two macronutrients, fat (glycerol moiety) and protein (glucogenic amino acids) which on their own confer flavors absent of sweet. The public should focus on consuming simple, fresh, and whole foods such as: fruits, vegetables, fish, lean meats, legumes, nuts, seeds, healthy fats, and whole grains and dairy products (with little or no added sugars). Naturally, these foods are in their least processed and most nutrient dense form. Although simple, less exciting and less promoted these foods are the backbone of all healthy diets. Eliminating sweetened beverages such as soda, sweet tea, flavored coffee, and even fruit cocktails can have a huge impact on lowering sugar consumption, reducing addictive tendencies to consume more sugar/calories, reduce weight gain, and of course delay the onset of disease. Processed foods do not need to be completely eliminated from the diet, but more so eaten in moderation, with the intent of eating mindfully. Furthermore, the importance of reading, understanding and taking into consideration food labels cannot be expressed enough. Promotion of good nutrition may not be as easily quantifiable as poor nutrition, however its hidden progressive outcomes can reshape the health of all future generations to come.

Reviewed by Christopher Blesso, Ph.D. Assistant Professor. Department of Nutritional Sciences. University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Great arcticle!